Plecotus auritus

The Brown Long-Eared Bat

Taxonomy

Plecotus auritus, also known as the brown long-eared bat, belongs to

the family Vespertilionidae of the order Chiroptera. Specifically, the species

is classified among the microchiroptera bats.

Geographical Distribution

The species is widespread in

Europe, with the exception of southern Spain, southern Italy, and Greece. It is

the second most common species of bat in Britain, although it is absent from

north and northwest Scotland. The

animal can also be found in India, Nepal, Mongolia, Siberia, China, Sakhalin,

Japan, South Korea, and the Himalayas.

Physical Characteristics

The average head-body length is approximately 37 to 48 millimeters, and

the wingspan ranges from 230-285 millimeters. The body weight of the animal

normally ranges from 5 to 12 grams. The females of the species are slightly

larger and heavier than the males. The adult bat has brown fur with a pale

underside and a pink-brown face, while juveniles are more gray in color

overall. P. auritus have relatively large eyes, and

slit-shaped nostrils that open laterally. The

most distinguishing features are the animalıs ears, which are nearly the length

of its whole body. When extended, the ear can be up to 25 millimeters

long. At rest, their ears are

tucked back and folded, resembling ram horns. When the animal hibernates, the

ears are tucked back so far that only the tragus is visible.

Habitat

The general habitat of P.

auritus is in sheltered valleys and

mountainous woodland. In the summer, the species roosts in barns, hollow trees, and old buildings. In

the winter, it can be found hibernating in caves, mineshafts, hollow trees, and

underground sites.

Roosting Behavior

Roosts provide the bats

shelter from the weather, protection from predators, and a warm environment for

rearing their young. Colonies typically consist of 10-20 adults, but can

contain as many as 50 individuals. Entwistle (1994) found that in May, the bat

colonies of the species were nearly all female, but the number of males

increased from June to September with a decease in the number of females and

juveniles. By October, males dominated the colonies. However, females tend to

remain in one roost all their lives, while males are more likely to depart to

another roost.

Diet and Foraging Behavior

The species is insectivorous,

and feeds primarily on moths. They also eat caterpillars, spiders, earwigs,

dung beetles, and flies. They forage at night, usually relatively close to

their roost. Foraging usually ends after about 4 or 5 hours. The bat catches

insects in flight or by foliage gleaning - picking insects out of trees or off

the ground. Gleaning is advantageous over aerial capture because moths cannot

as easily detect the bats presence so gleaning bats eats more moths than do

aerial hunters. Additionally, gleaners are less dependent on air temperature

and also they can catch non-flying prey like spiders and caterpillars. Aerial

hunters catch insects directly in their mouth, but also can use the tail and

wing membranes to scoop up moths or corral the insect toward the mouth. Also,

Plecotus auritus sometimes perform

steep somersaults techniques to catch prey. Plecotus bats not only fly in straight horizontal paths, but

also are known to hover, especially when gleaning for food from vegetation or

tree trunks. Figure 1 represents each type of flight.

Fig 1. Flight of the long-eared bat, Plecotus auritus. The position of the wings at each

of four 10-ms intervals is indicated by the numbers 1-4 on the dashed line.

This diagram represents the path taken by the wings during horizontal flight

(top, flight speed = 2.35 m/s) and hovering flight (bottom, flight speed = 0). (Norberg, 1976)

Hibernation

Prior to hibernation, in late

summer, the bats accumulate fat and this is used as an energy store for the

winter. Hibernation begins in November and ends in late March. When the bat is hibernating, the wings are folded

around its body, with its ears tucked under. Plecotus auritus typically hibernates in caves, tunnels, mines, buildings, and tree

holes. The animals prefer to hibernate at very cold temperatures, just above

freezing. They hibernate solitarily or in small groups. Premature disturbance

of hibernating bats can cause decreases in their population because it arousal

causes them to use up energy resources and in consequence they may run out of

energy and die before the end of winter. As a result, biologists and tourists

are restricted in how they observe the bats.

Mating Behavior

The male brown long-eared bat

has facial glands which produce a

brown, odorous secretion used to mark potential mating roosts. The male visits

as many roosts as possible to maximize its chances of mating, and marking

roosts helps to advertise their presence in order to attract females. P.

auritus is considered to show random,

promiscuous mating, where swarming occurs and females mate with many males.

Reproduction

The reproductive cycle of the brown long-eared bat is long - spermatozoa produced in one summer do not result in live young until the following summer. Males produce the greatest amount of sperm in late August/September and the mating period typically begins in October. Mating continues sporadically throughout the winter, but the maleıs sperm production ceases in November. Females delay fertilization until late April or May, after hibernation ends. This is when the female begins ovulation and sperm stored in the uterus fertilizes the ovum. The females then move into nursery roots (maternity colonies) and parturition takes place, usually in early July. The female gives birth to only one offspring per year (the length of one breeding season); twins are very rare. Because the reproductive cycle is long, complex, and only yields one infant, a female whose baby dies loses it chance to reproduce for a whole year. Fortunately, the species has evolved adaptations to minimize such failures, and studies have found that 70% (Entwistle, 1994) to 97% (Benzal, 1991) do produce young each year.

Long-eared bats are born

hairless, pink in color, and with their eyes closed. In the first week of its

life, the infant bat clings to its mother nipple. The baby is born with

incisors that have hooked tips to enable the animal to grip the nipple, even when

the mother is in flight. When the mother forages, the newborn bat is left

clinging to beams in the roost. By 4 days old, the baby has a covering of hair

and at 6 days old, the ears become erect and the eyes open. By 10-12 days,

babies begin to groom themselves and flap their wings. After 20 days, they can

fly around the roost, and by day 35, they first leave the roost on their own

wings. Weaning of the infant is complete about six weeks after birth.

The male Plecotus auritus reaches sexual maturity in the second summer of their

life. The female is sexually mature anywhere from 24-36 months of age. The

maximum age for the species is 30 years, but the average life span is seven

years for males, sixteen for females.

Echolocation

Because the echolocation

calls of Plecotus auritus are very

quiet, these bats are known as "whispering bats". I. Ahlen (1981)

described the calls as faint and short FM sweeps, about 2 ms long, and with

prominent second harmonics. Using quiet calls is beneficial to the animal

because the prey is less likely to detect its presence. The frequency of the

brown long-eared batıs call is usually 83-26 kHz, but sometimes louder at 42-12

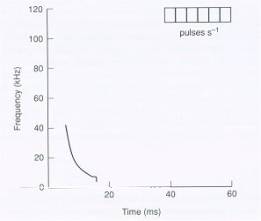

kHz. Figure 2 represents a loud-long sweep produced by Plecotus auritus.

Fig 2. Diagrammatic representation of the loud-long

sweep (Ahlen, 1981) of P. auritus

In general, CF signals, which increase the range of target detection, are used by the bats for hunting in open areas, while FM signals allow them to more accurately locate obstacles and targets in cluttered environments. Hence, gleaning bats use short, low-intensity FM signals to distinguish between insects and foliage while foraging.

Predation and Parasites

The habit of the brown

long-eared bat to fly close to the ground makes it vulnerable to attack by

predators, especially the domestic cat, Felis catus. Other predators include the barn owl (Tyto alba), the tawny owl (Strix aluco), and the kestrel (Falco tinnunculus).

Plecotus harbor relatively few ectoparasites, especially the

adults. This is believed to be connected with small colony size in these bats,

since fleas and mites cannot be transferred as easily. Also, the batıs tendency

to move from roost to roost further reduced the opportunity for parasite

populations to increase. As for internal parasites, Gardner et al. (1987) examined blood smears of P. auritus and found only one bacterium, Grahamella, which is transmitted by fleas and not harmful to the

host.

Relationship With Humans

P. auritus is considered to be very docile and one of the

easiest European species to handle and to tame. Their lives are greatly

entwined with those of human beings, as they utilize human homes and mine

shafts for shelter and protection. However, humans are more of a threat than a

positive influence to these bats. The most serious problem this species faces

is the loss of deciduous woodland due to large-scale farming. Other threats

include barbed wire, which bats can be impaled upon during foraging, deliberate

destruction of roots by pest exterminators, and disturbance from hibernation.

Plecotus auritus is not considered to be an endangered species, but

that does not mean it is without protection under the law. In Britain, bats are

protected under the Wildlife and Countryside Act of 1981, which states it is

illegal for anyone without a license to intentionally injure, kill, or even

handle a bat, to possess or try to sell a bat, or to disturb a roosting bat.

Europeans even set up bat boxes, or artificial roosts similar to bird nesting

boxes, for the bats to use. These bat boxes are popular with both the public

and bat enthusiasts because they are a practical method of protecting bats and

keeping them from intruding human homes.

Bibliography

Ahlen, I. (1981). Identification

of Scandinativan bats by their sounds.

Report No. 6, Dept. Wildlife Ecol. Swedish Univ. Agric.Sci.

Altringham, John D. Bats:

Biology and Behavior. New York: Oxford University Press Inc, 1996

Benzal, J. (1991). Population

dynamics of the brown long-eared bat (Plecotus

auritus) occupying bird boxes in a pine forest planation in central Spain. Neth. J. Zool., 41 (4): 241-249

Entwistle, A.C. (1994). Roost

ecology of the brown long-eared bat (Plecotus

auritus) in northeast Scotland.

Unpublished PhD thesis, University of Aberdeen, UK

Fenton, M. Brock, Just

Bats. Toronto: University of

Toronto Press, 1983

Gardner, R.A., Molyneux, D.H.

and Stebbings, R.E. (1987). Studies on the prevalence of haematozoa of

British bats. Mamm. Rev., 17 (2/3):

75-80

Neuweiler, Gerhard. The

Biology of Bats. New York: Oxford University Press Inc, 2000

Norberg, U.M. (1976). Aerodynamics,

kinematics, and energetics of horizontal flapping flight in the long-eared bat, Plecotus auritus. J. Exp Biol. 65:179-212

Norberg, U.M. (1976). Aerodynamics

of hovering flight in the long-eared bat, Plecotus auritus. J. Exp Biol. 65: 459-470

Nowak, Ronald M. Walkerıs

Bats of the World. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1994

Swift, Susan M. Long-Eared

Bats. London: T&AD Poyser Ltd, 1998