Species Account

Wahlbergıs Epauletted Fruit Bat

Epomophorus wahlbergi

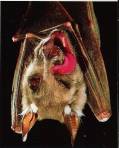

Wahlbergıs epauletted fruit

bat, or Epomophorus wahlbergi,

is a megabat, thus is of the suborder Megachiroptera and the Pteropodidae

family (Corbett 1986). Many

observers note that the head of Wahlbergıs epauletted fruit bat resembles that

of a dog, and most relate it to the head of a dachshund. However, the skeletal structure of

Wahlbergıs epauletted fruit bat reflects the primary function of the bat. The prominent keel on their sternum, or

chest bone, supports the major muscles used in flight. The muscles attached to this keel are

very powerful and are responsible for the swift movements of the long wings. This is important for the survival of

these bats, for they often travel as far as ten kilometers to find food. The wingspan of Wahlbergıs epauletted

fruit bat is about 508mm. This is

relatively long, for the total body length is usually between 125mm and 250mm

long, making the wingspan double or even triple the total body length. Wahlbergıs epauletted fruit bats

usually weigh between 40 and 120 grams (Kingdon 1974a). Compared to other bat species,

Wahlbergıs epauletted fruit bats have a simple wing structure. However, both the first and the second

digits of the foreleg are clawed.

Wahlbergıs epauletted fruit

bats are found in a variety of colors, the most common being grayish brown,

russet, or tawny in color (Nowak 1994).

These bats are named from the long tufts of white fur, or epaulets, that

sprout from their shoulders. Males

use their shoulder epaulets to attract females in courtship displays. Males also differ in appearance from

females, for males have air sacs in their necks. These sacs are used in food collection, as well as aid in

amplifying calls used to attract females during courtship (Nowak 1994). However, both sexes have white spots of

fur located at the top of the base of the ear. Located where the white ear spots and the shoulder epaulets

are found, Wahlbergıs epauletted fruit bats have scent glands. These glands produce a unique odor that

allows the bats to recognize one another.

The ear in Wahlbergıs

epauletted fruit bats is simple, for the outer ear has a basic oval shape,

forming an unbroken ring. The ear

also lacks a tragus. As does the ear,

the nose of Wahlbergıs epauletted fruit bat has a simple structure. These bats do not have a nose leaf, for

they do not rely totally on echolocation to navigate. Therefore, Wahlbergıs epauletted fruit bats have very large

eyes. They must rely heavily on

their sight, as well as smell, to navigate and identify their

surroundings. Due to their

frugivorous diet, their jaws are strong, and their teeth are adapted to best

process this fruit. Their cheek

teeth are large and flat, creating the perfect surface for chewing tough

fruit. Though they do not rely

totally on echolocation to navigate, the Wahlbergıs epauletted fruit bat may be

one of the four species of Megachiropterans that use echolocation to partially

orient themselves. Unlike other

echolocating bats, the sounds that these bats use are mostly audible to humans,

but do have ultrasonic components.

Also unlike other echolocating bats, the sounds are not produced in the

larynx, but are made by a clicking of the tongue on the back of the throat

(Lovett 30).

Wahlbergıs epauletted fruit

bat is native to Africa, and is found anywhere south of the Sahara desert

(Meester 1977). However, the

largest populations are in Cameroon and Somalia south to South Africa. Though these bats live in woodland and

savannah areas, they prefer the edges of forests (Kingdon 1974a). Summer brings a large migration to

Taaween, an area in the Zoutpansberg district of South Africa (Thomas

1983). The ripening crop of guavas

attracts these bats by the thousands.

During the daylight hours,

Wahlbergıs epauletted fruit bats live in hollow trees, underneath large leaves,

and beneath the eaves of buildings.

They often are found roosting where there is considerable light. Every few days, they will relocate to a

new roosting site (Fenton et al. 1985).

They roost in small groups containing mixed ages of both males and

females. The size of these groups

range from a few individuals to about one hundred individuals, depending on the

size of the roosting area (Wickler and Seibt 1976). They often revisit their previous roosting spots, at certain

times of the year, for many consecutive years. When roosting, they do not pack themselves tightly next to

one another; they will isolate themselves from their neighbors by short

distances, all while hanging from their feet in their roosts. While roosting, they remain relatively

quiet, and movement is at a minimum.

These bats seem to have a respect for each other, for they make it a

point to not intrude on each otherıs space.

As aforementioned, males use

their shoulder epaulets as a part of courtship. During the breeding season, the males congregate at

traditional sites, where they puff up their white shoulder patches, puff out

their cheek pouches, fan their wings and make repeated gonglike calls to attract

a mate, all in an attempt to get passing females to select them. The calls the male bats use to attract

females combines four short chirps, and is one second in duration. The pouches in the malesı cheeks are

inflatable sacs that act as a resonance chamber to enhance their calls. The males also use their long tufts of

hair and beating wings to help waft glandular odors that are attractive to

cruising females. The mating

procedures are extensive, all night events. An unusual aspect of this mating procedure is that the

females apparently need light to see the malesı courtship dance. Research shows that Wahlbergıs

epauletted fruit bats in Kenyan towns utilize the fabricated light from

streetlamps in Kenyan towns to provide sufficient light to allow males to court

all night long, even on moonless nights.

In most cases, Wahlbergıs

epauletted fruit bats bear a single young, but twins are occasionally

seen. After giving birth, the

mother carries her offspring clinging to her chest, as she forages for food. Females have one pair of mammary glands

located on the chest, from which they nurse their young. The male sexual organ resembles that of

some primates. Wahlbergıs

epauletted fruit bats mate twice per year on a seasonal basis, with births

occurring around the end of February, as well as the beginning of September

(Bergmans 1979a). Gestation lasts

from five to six months. When the

offspring are born, females are the only ones who rear the young, for the males

do not give assistance. Wahlbergıs

epauletted fruit bats do not scent mark their young, they recognize their own

young through vocalizations and olfaction.

Wahlbergıs epauletted fruit

bats are frugivorous, as indicated by their common name. The process by which they consume the

fruit is somewhat unique. They

chew the fruit, swallow the juice, and spit out most of the pulp and

seeds. They swallow some of the

softer pulp, as well as some of the seeds. The swallowed food goes through their simple monogastric

digestive tract, usually within half an hour. In order to get the fruit from the tree, these bats have

several methods. They either bite

the fruit while hovering; or they hang from a branch with one foot while using

the other foot to hold the fruit while they eat it; or they chop the fruit from

a branch by holding the fruit in their mouths, and making a twisting motion in

flight until the fruit drops off the stem. The structure of their lips and windpipe creates suction

that helps them to suck the juices from softer parts of the fruit. They also chew flowers to get the

nectar and juices. They feed

mainly on figs, mangoes, guavas, bananas, peaches, papayas, apples, and small

berries. The smell of ripening

fruit is what attracts them to their food source. Fruits are nutritious because they contain high quantities

of carbohydrates. Many fruits

contain fats, which are of benefit to the bat, in addition to the

carbohydrates.

Due to its frugivorous diet,

the Wahlbergıs epauletted fruit bat is a vital element in seed dispersal in the

tropics. The seedlings of most

tropical plants will not grow and mature in the shade of the parent plant. Therefore, the seeds must be carried

beyond the area where the parent plants are located. To add to that, fig seeds will not germinate without first

passing through the digestive tract of a bat or bird. Although many see bats as the local pests of the fruit

crops, they are invaluable in the preservation of the rain forests (Tuttle

557). After ingesting the seeds of

various fruits, these bats travel to areas where the seeds in their droppings

help expand the rain forest acreage.

However, this species is in

jeopardy from the perpetual human destruction of rain forests. As humans wipe out the tropical rain

forests of the world, these bats are forced to find new homes, often ones

closer to towns and cities. This

relocation poses a problem, for control measures, in the form of poisoned

fruit, are sometimes utilized in areas where the feed extensively on cultivated

fruit. Humans pose yet another

threat to bats. As we try to learn

more about these creatures, we continue to threaten their existence. The practice of bat banding is becoming

dangerous to many species of bats.

If the banding injures the delicate flight membranes, or even if the

banding causes stress to the bat, the batıs survival is threatened. In order for these animals to survive,

the public conception of bats must be permanently changed. Bats are a unique and irreplaceable

value to man and the ecosystems of the earth.

Works Cited

Bergmans, W. 1979a. Taxonomy and zoogeography of the fruit

bats of the People's Republic of

Congo,

with notes on their reproductive biology (Mammalia: Megachiroptera). Bijdragen

Tot de

Dierkunde. 161-86pp.

Corbet, G. B. 1986. A world list of

mammalian species. British Mus. (Nat. Hist.), London,

254 pp.

Fenton, M. B. 1975. Observations on

the biology of some Rhodesian bats, including a key to the

Chiroptera

of Rhodesia. Ontario Mus. Life Sci. Contrib., no. 104, 27 pp.

Kingdon, J. 1971a. East African

mammals. An Atlas of Evolution in Africa. London: Academic

Press.

341pp.

Lovett, Sarah. ³Wahlbergıs Epauletted Bat (Epomophorus

wahlbergi).² Extremely

Weird Bats.

New

Mexico: John Muir Publications. 30.

Meester, J. 1977. The mammals of

Africa: an identification manual. Smithson. Inst. Press,

Washington,

D.C. 37pp.

Nowak, R. 1994. Walkerıs Bats of

the World. Baltimore: Johns

Hopkins University Press. 66pp.

Thomas, D. W. 1983. The annual

migrations of three species of West African fruit bats

(Chiroptera:

Pteropodidae). Can. J. Zool. 2266-72pp.

Tuttle, M. ³Gentle Fliers of the

African Night.² National Geographic. Apr. 1986: 540-558.

Wickler, W., and U. Seibt. 1976.

Field studies of the African fruit bat Epomophorus wahlbergi,

with

special reference to male calling. Tierpsychol. 345-76pp.